The New York Times, October 5, 2003, Sunday

REAL ESTATE DESK

For Rental Buildings, A Rising Market

By ALAN S. OSER

PERSPIRING in his shirt sleeves on an August afternoon, Frank Pecora directed

the workers completing his new Italian restaurant in a building he bought on

First Avenue near 73rd Street. It opened on Labor Day as the new Delizia, next

door to the old Delizia, which was in space he had leased in 1983.

But Mr. Pecora, 52, is more than a restaurateur and no novice as a

real-estate investor. With a brother and other family members, he owns 23

buildings in Manhattan, most of them purchased since 1990. This year he bought

four of them, three in East Harlem.

They put him in the ranks of those who have been active buyers of

modest-sized rental buildings lately, a group that includes everything from

hands-on owner-managers like himself to nationally oriented real estate

investment trusts. Most of the buildings have fewer than 60 apartments, and

often they have commercial as well as residential space.

The buying comes at a time of favorable interest rates, if weaker rent levels

than owners had grown to expect before the events of Sept. 11. But lower rents

have not fazed buyers. They complain about a paucity of offerings. In New York

City, sales offerings are abundant mainly in hard times, when owners or their

lenders are driven to unload inventory.

Nevertheless, the buyers keep looking. The philosophy that drives them

differs, but Mr. Pecora's is a familiar one. ''For me, it's always a good time

to buy when I have the money,'' he said. ''I buy it and forget about it. In the

long run it has no way to go but up.''

Interviews with sales brokers and buyers themselves reveal that this

underlying faith is common. Since total rents in regulated buildings are usually

below market levels, some buyers are willing to forgo any return at all in the

early years of their investment, in the conviction that higher rental income

will eventually justify the prices they paid. Building improvements and other

changes in operations or occupancy may be needed to bring this about.

With certain properties producing incomes far below their potential, some

buyers have been willing to pay as much as 12 or 14 times the current rent roll

in Manhattan. That is not the norm, however. The more typical range in recent

sales in Manhattan is 9 to 12 times the annual rent, brokers and investors say.

To some extent these multiples reflect favorable mortgage-interest rates,

about 5 percent in recent years, but 6 percent or a more lately. As interest

rates decline, prices typically rise.

The concept of ''multiple of the rent roll'' is a standard way of speaking of

sale prices in rental buildings in New York City. It means, for example, that if

the average rent is $1,000 a month in a 60-unit building -- or rent of $720,000

a year, assuming full collection and full occupancy -- the building would sell

for $5.76 million at eight times the rent roll. At 10 times the rent roll the

same building would sell for $7.2 million.

''It's counterintuitive,'' said Robert Knackal, a principal in the sales

brokerage firm of Massey Knackal Realty Services. In general, he said, ''The

lower the rents the higher the upside, and the higher the upside the greater the

multiple of price to rents.''

Another factor in the current market, active buyers say, is that in recent

years some wealthy individuals have found real estate more appealing than the

stock market as a place to invest. ''Equity financing is easy to come by,'' said

Eric S. Margules, principal in Margules Properties, which has bought four

Manhattan buildings in the last two years.

Massey Knackal was the broker in the sale of a portfolio of 12 West Side

elevator buildings with 786 apartments this year. They sold for $109 million, or

11.28 times their total rents. These buildings had been held by the same family

for 80 years, Mr. Knackal said, and because of long-term occupancies, about 40

percent were renting at less than half of what they would rent for if vacant.

The new owner is Acquisition America L.L.C., in which Fred Shalom, president of

Empire Management, is a principal.

''We bought them for the long term,'' Mr. Shalom said. ''In 20 or 30 years

down the road, they will be valuable.''

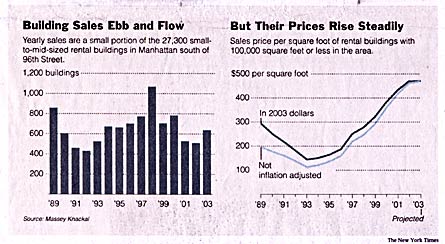

Manhattan Sales Trends

Prices Have Risen For a Decade

The Massey Knackal firm keeps statistics on sales of multifamily buildings.

One measurement has tracked sales of buildings under 100,000 square feet in

Manhattan south of 96th Street, with 27,300 buildings in the survey, since 1989.

Using rolling averages over a 12-month period, the firm found that the

average price rose to $465 a square foot in the 12 months that ended on June 30.

The rise has been consistent since a low of $115 a square foot in 1993.

Based of sales volume so far, the firm projects sales of 638 buildings this

year, or 2.3 percent of the 27,300 buildings. This would be a rise from 510

sales last year.

Prices, too, have risen markedly, although the figures suggest that since the

year 2000 the averages have hovered within consistent ranges: for elevator

buildings in Manhattan, between 10 and 12 times the rent roll; in Queens,

between 8 and 10; and in Brooklyn, between 6 and 8.

Walk-up buildings have lower average multiples -- between 9 and 10 in

Manhattan over the last three years, 7 to 9 in Queens and 5 to 7 in Brooklyn.

Elevator buildings are more sought after, Mr. Knackal said, since buyers usually

perceive a greater upside in them, so they will pay more.

The report has no information on the Bronx. One broker active in northern

Manhattan and the Bronx, Robert Chambrй of Chambrй & Company,

said multiples had risen to a range of 6 to 7.5 times the rent roll in the Bronx

and to 7 to 8 times in Washington Heights.

The New York City Finance Department also has numbers. They show increases in

values citywide. For example, in 2000 the average sale price of a residential

unit in rental buildings with 4 to 10 apartments in all Manhattan was $217,200;

last year the comparable figure was $223,000. In 1995 the figure was $86,000.

In these buildings the buyer is often planning to occupy one or more units,

or otherwise alter the property for personal use. Since considerations other

than pure investment are involved, the sale prices tend to be higher per unit

than they are in larger buildings. Finance Department figures show, for example,

that the average sale price per apartment in Manhattan buildings with 11 to 20

units last year was $115,600. In 1995 it was $40,800.

Other boroughs have also experienced increases in sale prices, but not of the

magnitude of Manhattan's. In Queens, for example, the average price per

apartment rose to $67,300 in 11-to-20-unit buildings last year, from $27,500 in

1995. In Brooklyn the comparable figures were $50,200 last year and $25,100 in

1995.

The buildings that are sold in any given year are only a tiny fraction of the

whole inventory. There were only 106 sales last year of 11-to-20-unit buildings

in Manhattan out of a total inventory of 5,500 such buildings. Citywide there

are 10,000 such buildings; only 250 of them were sold.

None of these figures take commercial space into account in mixed-use

buildings, so they somewhat distort true residential values.

Effect of Regulation

Building Owners Rely On Steady Rent Rises

Many sales are of buildings that are fully rent-regulated and are likely to

remain so even after vacancies occur. Tenancy turnovers in units rented below

their market value may run as low as 2 or 3 percent a year, and in very small

buildings owners may wait years for any turnover at all.

What the buyers are mainly relying on, they report, is the steady rise in

overall rents. Some believe these will average 6 to 7 percent a year over the

next few years, taking both vacancies and lease renewals into account. This

assumes that most of the apartments are currently renting well below vacancy

value.

Buyers and brokers say that the opportunity to deregulate an apartment once

it is vacated and the rent that a new tenant can legally be charged reaches

$2,000 has little effect on the sales market. However, under a law passed this

year, owners can achieve deregulation even if the owner is unable to get a rent

that high.

When a regulated tenant moves out or dies, an owner may achieve a legal rent

of $2,000 a month via the new-lease guideline increase, a vacancy allowance and

the rent increase permitted for apartment improvements. If significant

investment is needed to bring this about, it will be made if the owner believes

the unit is actually worth that much on the market, or soon will be.

At one time after the enactment of the Rent Regulation and Reform Act by the

State Legislature in 1993, regulations of the state Division of Housing and

Community Renewal freed the apartment from regulation only if the incoming

tenant actually paid $2,000 or more. But the law change allows deregulation even

if the tenant pays what the rent-stabilization code calls a ''preferential''

rent below that amount. Owners are required to inform incoming tenants of the

status of apartments that have become deregulated.

Mr. Knackal said that buyers of the buildings he sells in Manhattan often

assume their rent rolls will increase by an average of 10 percent a year in the

first few years of their ownership. This will come from a combination of

guideline increases, lease renewals, vacancy rent increases, major capital

improvements, more efficient operations and the new owner's ability to put a

stop to illegal occupancy. ''A lot depends on how neglectful the prior landlord

was in running the property,'' Mr. Knackal said.

But the range in building values is wide. Robert Shapiro, vice president of

Manhattan Property Investor Group L.L.C., said that in 13 deals in the last 16

months in which he was either a buyer or a seller prices ranged from 6 to 10

times the annual rent. The company is a short-term holder of properties, a deal

maker whose buyers include Mr. Pecora. ''The biggest factor in price is the

location of the property,'' Mr. Shapiro said.

Buyers also have to take into account the weakened rental market of the last

three years. Many owners told of a need to reduce vacancy rents from the levels

of three years ago. At the higher end of the market in particular, the vacancy

rate has risen. It is about 5 percent now in apartments that rented for upward

of $1,800 a month three years ago, estimated Nancy Packes, president of

Halstead/Feathered Nest Leasing Consultant. It was about 2 percent then, she

said.

But, as Martin Newman, a recent buyer on the West Side and East Side,

remarked, ''The juice in the sales market is the low-rent apartments.''

Mr. Newman, who buys property in partnership with Nathan Halegua, owns 33

buildings with 700 apartments and 46 stores in Manhattan, almost all south of

96th Street. He said that over the last 18 months he has profitably resold 11

buildings that he acquired between August 1999 and January 2001. He was able to

raise their rental income by an average of 30 to 35 percent through a

combination of rerenting vacancies, evicting or making settlements with low-rent

or illegal tenants, normal increases in stabilized rents and higher commercial

rents.

''There's a limit to how many buildings like this are available,'' Mr. Newman

said. ''And there's a limit to how much we would pay. I would not pay more than

10 times the gross rent -- maybe 11 in an elevator building.''

Tenant turnover is not necessarily what creates value, he said. At 589-593

First Avenue, at 34th Street, purchased three years ago, there has been little

turnover. But the rent roll has risen to $67,100 from $35,000 a month, largely

because he was able to cancel three store leases and rewrite them, he said. The

tenants stayed.

Another successful recent investment involved a property on the southwest

corner of Second Avenue and St. Marks Place in the East Village -- three

contiguous six-story walk-up buildings with 64 apartments and 11 stores, three

of them little more than kiosks. The property was purchased for $7.6 million in

1998, when the total rents were $1.07 million. The buyers projected a rent roll

of $1.35 million in five years.

After five years, rents have actually reached $1.54 million, Mr. Newman said.

The rise in residential rents was the principal reason in this instance. The

turnover of 12 apartments, through a combination of deaths, buyouts and

eviction, accounted for roughly half the growth in the residential portion of

rent roll, which itself accounts for about half of total rental income.

''We still have tenants paying $300 a month and a couple are using toilets in

the hall,'' Mr. Newman said. But once vacated and upgraded, a typical

one-bedroom apartment will rent for $1,500 to $1,800 a month, he said.

Dealing With Tenants

In Shared Spaces, Owners' Opportunity

In Manhattan buildings, a significant percentage of newly arriving tenants

are sharing, and the rents are coming from two, three or four individuals. Many

sharers have gone into buildings owned by Baruch Singer and his partners. Mr.

Singer, who operates 2,500 apartments in moderate-rent locations, says he has

bought 20 buildings in the last three years. More than 40 percent of the new

arrivals in his buildings are apartment sharers, he said. Of the rest, half are

one-person households.

One recent purchase was the 55-unit building at 894 Riverside Drive, at 160th

Street, near Columbia Presbyterian Hospital.

He paid 10 times the rent roll there, he said, because the average rent was

much lower than what would normally be expected. He suspected a high degree of

illegal activity.

''From my experience, 10 to 15 percent of the tenants are illegally renting

out rooms,'' Mr. Singer said. It is not unusual for the tenant to be collecting

$1,200 a month in an apartment in which the landlord is collecting $400, he

said. On some occasions the tenant has ''sold'' the apartment and moved out. The

new ''tenant'' pays the rent with money orders using the name of the tenant on

the lease.

Mr. Singer's efforts to evict these tenants keep his lawyers in Housing

Court, where he estimates he initiates about 100 actions a year. The outcome is

mixed, he said. Some tenants leave, some settle and some are evicted.

But most buyers appear unwilling to pay prices predicated on their ability to

gain possession of low-rent, possibly illegally occupied, apartments. There are

other ways to add value. Mr. Margules, who owns 43 buildings with 800 apartments

owned through various partnerships, said that there was little illegal occupancy

in the buildings he had bought in the last two years, but considerable

opportunity for adding value.

In one case he was able to negotiate a settlement of a harassment complaint

against the former owner that was impeding rent collections, he said. In another

case he was able to change the status of a single-room-occupancy building to a

rent-stabilized building.

At 43 Clinton Street, on the Lower East Side, he bought a dilapidated 18-unit

building with two stores four years ago. It had six vacancies and a need for

$100,000 in structural and apartment improvements. Now he is able to get $1,500

a month for vacant one-bedroom apartments, usually from two sharing tenants, he

said.

Many of the new owners know at least some of their tenants personally. But

that is not likely to be the case with the executives of the Denver-based

Apartment Investment Management Company, a publicly listed real estate

investment trust known by the acronym Aimco, a recent buyer of residential

property in Manhattan.

Last March Aimco bought 311-313 East 73rd Street, two 1920's walk-ups with 35

apartments, a sale that pointed up the interest of a national real estate

company even in a Class B property in the city if it is well located. Aimco's

2002 annual report says that its portfolio includes 1,800 properties with

318,000 housing units.

This year Aimco bought 181-199 Columbus Avenue, a strip of older buildings on

the east side of the avenue between 68th and 69th Streets, with 12 stores and 88

walk-up apartments. The price was $37.5 million.

''When rents are down in a lot of cities,'' said Georgia J. Malone, who

represented Aimco in both purchases, ''national companies like New York

properties, because the rents are stable in regulated buildings even when market

rents weaken.''

But competition from large buyers does not worry hands-on owners like Frank

Pecora, the restaurant owner who buys small buildings in Manhattan. ''I have an

advantage on them,'' Mr. Pecora said. ''I don't depend on contractors. I don't

depend on other people. I depend on myself.''

Published: 10 - 05 - 2003 , Late Edition - Final , Section 11 , Column 5 ,

Page 1

Correction: October 12, 2003, Sunday An article last Sunday about the

market for smaller rental buildings misspelled the name of a principal in a

sales brokerage firm as well as the firm name, which was also misstated in the

credit line of a chart. The executive is Robert Knakal, not Knackal; the firm is

Massey Knakal.

Copyright New York Times, 2003

|